The Cynefin Framework applied to Data Governance

Phil Jones, Enterprise Data Governance Manager, Marks & Spencer

When I first got involved in data governance I found the breadth, depth, diversity, and complexity of the subject matter somewhat overwhelming, particularly on where to start, how to get it done, and how to introduce change that would stick.

My background is in business process architecture with some project management experience, so I set about applying these trusted techniques: they had worked for me in the past, after all, so why not now? I figured that the underlying causes of the data quality issues that I needed to fix were related to failures of understanding and on process adherence. My plan was to do detailed analysis to find a “one best way”, and then implement change supported by KPI measurement. I saw some progress, but it became apparent that my preferred approaches to problem solving were not sufficient, particularly when I started to encounter the need for behavioural and cultural change.

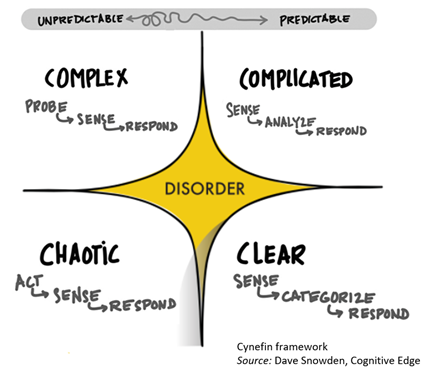

It was about this time that I came across the Cynefin framework. Cynefin [ku-nev-in] was developed by Dave Snowden in 1999 and has been used to help decision-makers understand their challenges and to make decisions in context. It has been used in a huge variety of scenarios: strategy, police work, international development, public policy, military, counterterrorism, product and software development, and education. This blog is my attempt to apply Cynefin to Data Governance.

What is the Cynefin Framework[1]?

Cynefin provides a framework by which decision makers can figure out how best to approach a problem, helping us to distinguish order from complexity from chaos. It helps to avoid the tendency for us to force a “one size fits all” approach to fix problems, best explained by Maslow: “if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail”.

What does the Cynefin framework look like?

The framework is made up of five situational domains that are defined by the nature of the cause-and-effect relationships: clear, complicated, complex, chaotic, and disorder:

The “Clear” Domain: the domain of best practice

The relationship between cause and effect exists, is repeatable and is predictable. This is the realm of “known knowns” and decisions are not questioned as there is a clear approach to follow. The approach that you apply to a problem or decision within the Clear domain is:

Sense à Categorise à Respond

- You Sense the problem that you are faced with

- You Categorise it: determine the category of problem that it sits within

- Based on this categorisation you then Respond with the appropriate response

This is the domain of best practices: each time you encounter a problem of a certain category you follow a script that guides you through to the resolution of that problem with a high level of confidence of a positive outcome.

|

I am a keen cyclist. A problem that I encountered on a recent ride was a puncture. Sensing a puncture is not so difficult: the bike becomes slightly wobbly, and you can feel the metal rims of the wheel impacting on the road. Categorising the problem takes seconds: pinching the tyre confirms the issue. Based on this problem categorisation I responded by following a clear and well-established routine – a best practice – to fix the puncture so that I could continue my ride.

|

The Complicated Domain: the domain of good practice

There is still a predictable relationship between cause and effect, but there are multiple viable options available. This is the realm of “known unknowns”, is not easy to do and often requires effort and expertise. There is not a single “best practice”; there are a range of good practices: problems in this domain require the involvement of domain experts to select the most viable approach. The approach that you can take to a problem or decision within the Complicated domain is:

Sense à Analyse à Respond

- You Sense the problem that you are faced with

- You then Analyse the problem

- Based on the outcomes of the analysis you then Respond with the appropriate response

|

To illustrate this with another cycling analogy: my bike recently developed an annoying squeak that I couldn’t fix. A friend who knows far more about bikes that I do came up with a couple of ideas but neither of them worked, so I went to a bike shop where the mechanic did a more thorough inspection and was able to isolate the problem: a worn bottom bracket. I sensed the problem – the squeak – I sought the advice of experts to analyse the problem. My response was to apply the most viable option using good practice to fix the squeak. I can now ride with a greater amount of serenity.

|

The Complex Domain: the domain of emergence

The Complex domain is where the relationship between cause and effect potentially exists, but you can’t necessarily predict the effects of your actions in advance: you can reflect in hindsight that your actions caused a specific effect, but you weren’t able to predict this in advance, and you can’t necessarily predict that the same action will always cause the same effect in the future. Because of this, instead of attempting to impose a course of action with a defined outcome, decision makers must patiently allow the path forward to reveal itself: to emerge over time.

The approach that you can take to a problem or decision within the Complex domain is:

Probe à Sense à Respond

- You Probe the problem that you are faced with a set of experiments

- You then Sense the reaction that the experiment garners

- If there is a positive reaction, then you Respond by amplifying the experiment; if there is a negative reaction then you dampen the experiment

This is the domain of emergent practices and “unknown unknowns”. You test out hypotheses with “safe to fail” experiments that are configured to help a solution to emerge. Many business situations fall into this category, particularly those problems that involve people and behavioural change.

|

When Ken Livingston announced a scheme to improve transport and the health of people in London in 2007, he said that the programme would herald a “cycling and walking transformation in London”. Implementing this has largely followed the Complex approach: transport officials studied schemes in Paris and elsewhere and considered the context of the problem in London. They talked to (probed) commuters, locals, and visitors to better understand people’s attitudes and behaviours related to cycling. They assessed the constraints imposed by the existing road network, and a range of other challenges, from which they came up with a limited “safe to fail” trial.

The scheme launched in 2010 in a localised area and the operators of the scheme assessed (sensed) what worked and responded by applying adjustments. For example, the initial payment process required access keys; this was replaced by users of the scheme having to register on an app. The scheme has continuously evolved with further innovations: it has followed an emergent approach, with successful changes amplified and those less successful dampened. The scheme as of today is different from where it was when first launched, and it will continue to evolve.

|

The Chaotic Domain: the domain of rapid response

The Chaotic domain is where you cannot determine the relationship between cause and effect: both in foresight and hindsight: the realm of “unknowable unknowns”. The only wrong decision is indecision. We come into the Chaotic domain with the priority to establish order and stabilise the problem, to “staunch the bleeding” and to get a system back on its feet. We don’t have time to look up a script: the problems we are seeing have not been experienced before; we can’t call up experts and rely on best practices; we can’t devise a set of experiments to see if we can emerge a new practice to tackle the problem. The approach that you can take to a problem or decision within the Chaotic domain is:

Act à Sense à Respond

- You Act immediately and decisively to stabilise the system and address the most pressing issues

- You then Sense where there are areas of stability and where they are lacking

- You then Respond accordingly to move the situation from chaos to complexity

The practices followed in the Chaotic domain are novel practices in which you move quickly towards a crisis plan with an emphasis on clear communications and decisive actions.

|

An example of where cyclists experience chaos are the mass crashes in events such as le Tour de France. An accidental touching of wheels or an errant spectator can bring down the whole peloton, resulting in cyclists and bikes strewn across the road. The immediate priority is to act: who is injured? Medics triage and act to look after those in pain. Are the bikes in one piece? Mechanics act by applying fixes or replacing broken bikes. All of this is done in a matter of seconds.

With the casualties being looked after, those in a position to continue sense what to do: if their team leader is down, what should the team do? They don’t put out an urgent request for white boards and assemble for a team meeting: the race is not going to wait for them. They get back on their bikes and work out their response and get on with it, and then adapt their approach as required. They may form temporary alliances with other teams to catch back up with the main peloton: they have come up with some novel practices and have been able to get some semblance of order out of chaos.

|

The Disorder Domain: the domain of emergence

Disorder is the state that you are in when it is not yet clear which of the other four domains your situation sits within, or you are at risk of applying your default approach to problem solving irrespective of the nature of the problem. The goal is to best categorise your problem into the most appropriate domain as quickly as possible.

Movement between domains

The framework is dynamic in nature in that problems can move between domains for many reasons. The guidance within Cynefin is that the most stable pattern of movement is iterating between Complex and Complicated, with transitions from Complicated to Clear only done when newly defined “good practice” has been sufficiently tested as “best practice”.

Beware of complacency

Clear solutions are vulnerable to rapid or accelerated change: the framework calls out the need to watch out for the movement of a problem from Clear to Chaos. There is a danger that those employing best practice approaches to problem-solving become complacent: they assume that past success guarantees future success and become over-confident. To avoid this, Clear problem-solving approaches should be subjected to continuous improvement, and mechanisms should be made available to team members to report on situations where the approach is not working.

|

There was one time when I fixed a puncture but was then distracted, or complacent, when putting the wheel back on the bike. I found this out to my cost when I was going down a hill and lost control of the bike – a chaotic event, at least for me. Fortunately, I landed on some grass and only my pride was wounded. Having learnt my lesson I now double-check that everything is okay before setting off.

|

Where does Data Governance sit within the Cynefin framework?

Dealing with Chaos

Snowden states that “there has never been a better chance to innovate than in a major crisis … where we need to rethink government, rethink social interactions, and rethink work practices. These must take in place in parallel with dealing with the crisis”. We have all had to innovate throughout the recent Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns: for example, how to collaborate on managing data in an effective way when we are all working remotely; how to best onboard new joiners and provide them with an understanding of the data they need to perform their roles. In my team we acted quickly to come up with some novel solutions and have adapted them over time.

Complex

According to Snowden, many business situations fall in the Complex and Complicated domain areas. Anything involving people change, such as changes to behaviour or to organisational culture, sit in Complex. It is widely agreed that behavioural and cultural change are the most challenging aspects of Data Governance. Nicola Askham, the Data Governance Coach and DAMA committee member, makes this point really well in a blog (link) where she discusses “the biggest mistake that I have seen is organisations failing to address culture change as part of their governance initiatives … This mistake … can ultimately lead to the complete failure of a data governance initiative”.

To add to this view, in a recent open discussion in social media another DAMA committee member, Nigel Turner, positioned two key features for successful data governance programmes that apply to any organisation: firstly, that “it must be unique to each [organisation] as it must be embedded within the existing cultural and organisational context of that organisation … one size does not fit all”. Secondly, when considering the challenges of engagement and adoption: “how do I get business buy in? How do I appoint data owners and data stewards? How do I demonstrate the benefits of data governance? How do I prioritise potential data improvements?”

These opinions from highly respected data governance professionals place those components of data governance related to people change within the Complex domain where, as we have learnt from earlier, the approach is to probe, sense, and respond.

Complicated

In the domain of good practice, my team in Marks & Spencer have developed a range of good practices which can be applied by subject matter experts (SMEs) to a problem. For example, we have developed a “Data Governance by Design, by Default” and a “Data Quality Remediation Approach” good practice guides that SMEs can refer to when tackling problems and opportunities of this nature. Both good practice guides are informed by our Data Principles and Policies, which also sit within the Complicated domain: the principles and policies are directive and require a certain amount of effort and expertise to apply. All these artefacts are subject to continuous improvement.

Clear

In the domain of good practice, the focus is on developing repeatable patterns to apply the appropriate response any time when the situation is encountered. In M&S we have developed automated processes to perform data quality checks at scale against specific business rules, and to automatically tag datasets to support information classification. These rule sets were carefully constructed and tested, and only moved to the Clear domain when they were approved; however, this is not a “fire and forget” approach: we monitor the performance and the currency of the rules to ensure that they remain fit for purpose.

Conclusion

When you’re next faced with a problem, question whether the approach that you are about to apply is appropriate: does the problem really sit in best or good practice, or do you need to do some probing, sensing, and responding? And when you are working on a problem in the Complex domain, how comfortable are you to create environments and experiments that allow patterns to emerge in the face of pressures for rapid resolution of the problem and a move to command and control?

You can also use the framework to challenge those who claim that complex problems have simple solutions and recognise where their biases are leading them to misdirected and constrained thinking. For example, people who prefer to operate in the Clear domain may try and impose KPI measurement for what is a Complex problem. This can result in the undesirable behaviours of the gamification of the KPIs and thereby giving a false sense of progress, rather than addressing the underlying problem.

Cynefin has really helped, and continues to help, the work that my team is doing in Data Governance where the problems we face manifest themselves across all five domains. By understanding the characteristics of a problem we can rapidly apply the best approach to properly understand the problem and then work out how best to set about fixing it.

Dave Snowden is highly altruistic in how he shares his ideas and his expertise: I encourage you to visit his website Cognitive Edge (cognitive-edge.com) for further resources, and there is a load of video content online. I can particularly recommend his commentary on hosting a children’s party: highly amusing.

If you have applied Cynefin to help fix a problem already, or after reading this blog, it would be great to hear from you.

[1] Content relating to the Cynefin framework in this blog has largely been sourced from Dave Snowden’s excellent book: “Cynefin – Weaving sense-making into the fabric of our World”, and his many articles and online videos. The examples provided relating to bikes and data governance are mine alone, as are any errors.